Nutrition & Health Info Sheets contain up-to-date information about nutrition, health, and food. They are provided in two different formats for consumer and professional users. These resources are produced by Dr. Rachel Scherr and her research staff. Produced by Anna M. Jones, PhD, and Rachel E. Scherr, PhD.

What is the National School Lunch Program?

The National School Lunch Program was created in 1946 through the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act to provide nutritious, low-cost school lunches to children in the United States [1]. It is administered through the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which reimburses schools a set amount for each meal served, provided they adhere to minimum nutrition standards and are provided at no- or reduced-cost to children unable to pay the full cost [1]. In addition, the meal programs are required to be non-profit, and cannot discriminate against children receiving free or reduced-price meals.

What are the requirements for lunches served in the NSLP?

All lunches served need to follow the meal pattern, which specifies the food groupings and amounts to be provided as well as the calorie range the meals must fall within [4]. The amounts required and calorie ranges vary by age and grade grouping (Table 1). In addition, meals must include zero grams of trans fat, provide less than 10 percent of calories from saturated fat, and fall within current sodium targets. Target 1 went into effect July 1, 2014, with Targets 2 and 3 to go into effect July 1, 2017 and July 1, 2022 respectively. However, implementation of Targets 2 and 3 have been delayed, as described below.

Table 1: Meal pattern requirements for each age/grade grouping [4].

|

|

Grades K-5 |

Grades 6-8 |

Grades 9-12 |

|

Fluid Milk |

8 fluid oz |

8 fluid oz fat-free or low-fat milk |

8 fluid oz fat-free or low-fat milk |

|

Vegetables Subgroups: Dark Green Red/Orange Beans and Peas Starchy Other |

¾ cup per day

½ cup per week ¾ cup per week ½ cup per week ½ cup per week ½ cup per week |

¾ cup per day

½ cup per week ¾ cup per week ½ cup per week ½ cup per week ½ cup per week |

1 cup per day

½ cup per week 1¼ cup per week ½ cup per week ½ cup per week ¾ cup per week |

|

Fruit |

½ cup per day |

½ cup per day |

1 cup per day |

|

Grains |

1 oz-eq per day 8-9 oz-eq per week |

1 oz-eq per day 8-10 oz-eq per week |

2 oz-eq per day 10-12 oz-eq per week |

|

Meat and Meat Alternate |

1 oz-eq per day 8-10 oz-eq per week |

1 oz-eq per day 9-10 oz-eq per week |

1 oz-eq per day 10-12 oz-eq per week |

|

Sodium Target 1 Target 2 Target 3 |

≤ 1,230 mg ≤ 935 mg ≤ 640 mg |

≤ 1,360 mg ≤ 1,035 mg ≤ 710 mg |

≤ 1,420 mg ≤ 1,080 mg ≤ 740 mg |

|

Calorie Range |

550–650 cal |

600–700 cal |

750–850 cal |

Many manufacturers produce modified versions of their popular products that comply with school meal regulations, which may lead to some confusion among consumers. An example of the difference between products sold to the consumers versus products sold to schools is Domino’s Smart Slice.

A slice of Domino’s Smart Slice with pepperoni is made with whole grain-rich crust, mozzarella with reduced fat and sodium, and pepperoni with reduced fat and sodium. As a result, the Smart Slice contains fewer calories, less fat and saturated fat, and less sodium when compared to a standard slice of Domino’s pizza (Table 2). While reformulated versions of products meet school meal pattern requirements, some argue that these types of products do not align with efforts to encourage healthier eating habits as they may result in children seeking out the consumer versions on store [7].

Table 2: Comparison between Domino’s Smart Slice and standard pepperoni pizza slice

|

|

1 Slice of 14” Smart Slice with Pepperoni and Cheese [8, 9] |

1 Slice of 14” Hand Tossed with Regular Cheese and Pepperoni [10] |

|

Calories |

260 |

300 |

|

Saturated Fat (g) |

4 |

5 |

|

Sodium |

510 |

720 |

How are requirements for school lunches developed?

The National School Lunch and School Breakfast Program are part of a larger set of programs that are reauthorized by Congress approximately every five years, although the most recent Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act, known as the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA), was passed in 2010 [11]. The development of the regulations must follow procedures laid out in the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946 (APA) [12].

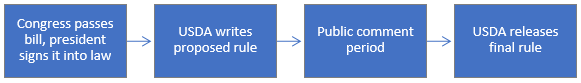

In brief, once the Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act is signed into law, the administrating agency, the USDA, drafts the proposed rule, which is then available for public review and comment. Following the public comment period, the USDA reviews and synthesizes the comments received. Revisions are made based on these public comments and the final rule is released (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Process by which NSLP regulations are developed.

In some situations, the USDA implements interim rules that are also subject to the APA and must undergo a public comment period before the final rule can be released.

In early 2020, a federal judge struck down a final rule that had gone into effect in 2019 because it deviated too far from the interim rule [13]. According to the ruling of the judge in this case, the final rule and the interim rule differed with respect to grains and sodium (Table 3); as a result, the public was not permitted an opportunity to comment on the changes that were implemented in the final rule [13].

Table 3: Comparison of the HHFKA Final Rule to the interim and final rules for Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements.

|

Impacted Standard |

HHFKA Final Rule [4] |

Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements Interim Rule (Announced 2017, in effect July 1, 2018) [14] |

Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements Final Rule (Announced 2018, in effect February 11, 2019 - 2020) [15] |

|

Milk |

Low-fat plain and fat-free flavored milk allowed |

Low-fat flavored milk allowed in addition to low-fat plain and fat-free flavored |

Low-fat flavored milk allowed in addition to low-fat plain and fat-free flavored |

|

Grains |

All grains must be whole grain-rich |

States permitted to issue waivers to SFAs experiences difficulties in meeting whole grain requirements |

50% of gains must be whole grain-rich |

|

Sodium |

2014: Target 1 – 1360 mg 2017: Target 2 – 1035 mg 2022: Target 3 – 710 mg |

Target 1 maintained through 2020 school year |

Implementation of Target 2 postponed until 2023-2024 Target 3 eliminated |

What foods are students required to take?

While schools are required to offer all of the components included in the meal, Offer versus Serve (OVS) is a provision of the NSLP that allows students to decline to take some of the food offered while still permitting the school to receive the full reimbursement for that meal. This program was introduced in the 1970’s as a way to reduce costs and food waste (5). Under OVS, the student must take three of the five components offered, and one of those must be at least ½ cup of fruit or vegetable in order for the meal to be reimbursable [16].

Offer versus Serve is required for grades 9-12, but is optional for all other grade groupings. If a school does not opt to implement OVS in younger grade groupings, then all five components must be offered and taken by the student [16].

What is the difference between free, reduced-price, and paid meals?

There are no differences in the meals served, however the income eligibility for participants and reimbursement amounts schools receive from the USDA differ for each (Table 4). These rates are adjusted annually.

Table 4: Eligibility criteria and lunch reimbursement rates for the 2020-2021 School Year for schools in which less than 60% of the meals served in the previous year were free or reduced-price [17].

|

Description |

Free |

Reduced-Price |

Paid |

|

Reimbursement Rate |

$3.58 |

$3.18 |

$0.40 |

|

Income Qualification |

< 130 percent of the federal poverty guidelines |

130-185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines |

None |

Students qualify for free or reduced-price meals through an application completed by a parent or guardian. Two programs created to reduce administrative burden with regard to applications include direct certification and community eligibility provision (CEP).

Direct Certification

Children whose families participate in other income-based programs can be directly certified to receive free school meals [11]. For example, a student whose family receives Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits would also be eligible for free school meals and identified as such through data sharing between programs.

Community Eligibility Provision

In schools or districts in which a large proportion of students are identified as eligible, the SFA can opt for community eligibility provision (CEP) . This allows the SFA to serve free meals to every student [11]. In order for a school or district to be eligible, 40 percent or more of the students need to identified as automatically eligible (for example, through direct certification). Based on a funding formula established by the USDA, schools receive reimbursement at the free meal rate for a certain percentage of their students, while the remainder of meals are reimbursed at the paid rate [11].

What about other foods that are sold on campus?

Any food that is sold to students during the school day (midnight before the school day to 30 minutes after the end of the school day) outside of school meals is considered a “competitive food” and is subject to Smart Snacks in Schools requirements [18]. This includes foods and beverages sold a la carte in the cafeteria, in vending machines, school snack bars or stores, or as part of fundraisers (if the food is being sold to students to be consumed on campus). These requirements do not apply to foods that are not sold to students.

Smart Snack requirements include general nutrition standards. These require foods sold to either be a whole grain product, or be made from fruits, vegetables, dairy products or protein foods, as well as meet minimum nutrient standards for calories, sodium, sugar, fat, and saturated fat. These nutrients are different whether a food is classified as a snack versus an entrée. Certain foods are exempt from these standards, such as nuts, which are exempt from total fat and saturated fat requirements.

Beverages are limited to flavored and unflavored low-fat and fat-free milk, 100% juice, and 100% juice that is been diluted with water but contains no added sweeteners. High schools are also allowed to sell low- and no-calorie beverages such as flavored water and diet soft drinks (with or without caffeine), provided they meet limits on calories.

How do school lunches compare nutritionally to packed lunches from home?

Research suggests that school lunches on average contain more fruits and vegetables than lunches from home even in studies conducted prior to the HHFKA went into effect, which mandated increased amounts of fruit and vegetables, as well as increased whole grains and reduced sodium. Lunches from home also tend to include foods that are restricted in school meals, such as sugar-sweetened beverages and snack foods such as potato chips.

One study, conducted with fourth and fifth grade students in two suburban schools in Minnesota found that those consuming school lunch consumed significantly fewer calories, grams of fat, and grams of added sugar, while consuming more vegetables than students brought lunch from home [19]. This study also reported that students eating school lunch consumed more sodium and fewer whole grains than those who brought lunch from home; however, these data were collected before the HHFKA went into effect in 2010.

In a study conducted in three schools in Northern California that focused on fruit and vegetable consumption, packed lunches contained fewer fruits and vegetables than school lunch and students with packed lunches consumed fewer fruits and vegetables than those that consumed school lunch [20]. Other studies have also reported fewer vegetables in packed lunches compared to the NSLP requirements , as well as including foods such as sugar-sweetened beverages, snack foods, and desserts [21].

How has school lunch changed over time?

As nutrition science has evolved and population needs have shifted, so have school lunch meal patterns. When the NSLP began in 1946, undernutrition and insufficient calories were a greater concern, while today the obesity epidemic is a much more pressing issue.

1946

In 1946, school meals were required to include the following [22]:

- 8 ounces of fluid milk with minimum fat content

- 6 ounces of fruit or vegetables

- 1 portion of bread, muffin, or other hot bread made of whole-grain or enriched flour

- 2 ounces of meat, poultry, fish, or cheese; or ½ cup of beans; or 4 tablespoons of peanut butter, or 1 egg

- 2 teaspoons of butter or fortified margarine

1958

Starting in 1958, school meals were required to include two vegetable and/or fruit items; previously, the required 6 ounces of fruit or vegetables could be a single item [22].

1970s

In the 1970s, school meals were permitted to include low-fat or nonfat milk and the requirement to serve butter or margarine was eliminated. Minimum amounts of the different components (Milk, Fruits/Vegetables, Grains, Meat/Meat Alternate) were specified for different age groups and a requirement to meet 1/3 of the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) was added [22].

In addition, Offer versus Serve (described above) was introduced during this time [23].

1990’s

A greater focus on improving the healthfulness of school meals emerged in the 1990s, with requirements that school meals reflect the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. This included requirements that fat could not exceed 30 percent of calories, while saturated fat was limited to less than 10 percent of calories[22]. The 1989 RDAs used for minimal standards for key nutrients, which included protein, calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C [22].

2010

The Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act resulted in increased daily servings of fruits and vegetables, as well as weekly requirements for vegetable subgroups. Other requirements included serving whole grain-rich grains, maximum levels of sodium, and maximum calorie levels.

What are other requirements that school meal programs have to meet?

As a federally-funded and regulated program, the NSLP is subject to many regulations beyond that of the meal pattern. This includes regulations related to documentation, food safety, fiscal management and responsibility, procurement, indirect costs, among others. Compliance with regulations is assessed every three years as part an Administrative Review (AR).

A thorough review of regulations within the NSLP is outside of the scope of this information sheet, however there are two requirements that are more visible to the general public, either due to news coverage, as is the case with cafeteria fund, or required public involvement, as is the case with the Local School Wellness Policy mandate.

Cafeteria Fund

The cafeteria fund is a required and restricted account for all school meal program revenue and expenses. The code of federal regulations states that “Revenues received by the nonprofit school food service are to be used only for the operation or improvement of such food service” [24].

In the past several years, news articles tangentially related to the cafeteria fund have arisen around the issue of what is referred to as “lunch shaming.” In some instances, these news stories involve lunches of students be thrown away after it is determined they are unable to pay [25], in others, they involve school employees being reprimanded or their employment terminated after providing meals to students who were unable to pay [26].

The reasons behind these stem from the restricted nature of the cafeteria fund. All meals that are provided must be accounted for, either as free, reduced-price, or paid. The procedure for when a student does not qualify for free lunch and is unable to pay varies, but may involve allowing a student accrue a certain amount of unpaid meals while the school contacts the parents or guardians to resolve the account. If over time the meals still go unpaid then it becomes what is called “bad debt.” The code of federal regulations states that “Bad debts, including losses (whether actual or estimated) arising from uncollectible accounts… are unallowable” [27]. This includes unpaid meal charges. As a result, the district needs to cover “bad debt” from non-federal funds.

Local School Wellness Policy

The Local School Wellness Policy (LSWP) was initially mandated in 2004 in response to concern about rising obesity rates in children [28]. All districts participating in the NSLP were required to establish a local school wellness policy that included the following elements:

- Goals for nutrition education, physical activity, and other activities to promote student wellness;

- Nutrition guidelines for foods and beverages available on campus;

- Guidelines for school meals that align with federal meal requirements;

- A plan for measuring implementation; and

- Involvement of parents, students, school meals program representatives, school board and school administrators, and the public in the wellness policy committee.

The HHFKA further strengthened the LSWP requirements by including additional wellness policy requirements [29]:

- Identifying leadership to ensure schools within the district comply with the policy;

- Informing the public of about wellness policy and its implementation;

- Using evidence-based strategies to determine nutrition education, physical activity, and other wellness goals;

- Nutrition guidelines for all foods and beverages sold on campus that align with Smart Snacks in Schools;

- Policies for other foods and beverages available on campus (such as incentives, classroom celebrations, and fundraisers); and

- Description of how the public will be involved and updated of progress, policy leadership, and policy evaluation plan.

How do state and local regulations factor into the NSLP?

While the federal requirements set by the USDA apply to all participating SFAs nationwide, states and local governments often implement more stringent standards or additional regulations provided they do not result in lower standards than what is required federally. For example, California has enacted the following:

- Stricter competitive food standards compared to Smart Snacks in Schools. For example, All beverages sold must be caffeine-free, while caffeine is allowed in beverages sold in high schools under Smart Snacks in Schools requirements [30].

- Unpaid meal debt policy. The Child Hunger and Prevention Fair Treatment Act of 2017 (amended in 2019) states that schools cannot deny a student a school meal, offer an alternative meal (unless needed for dietary or religious reasons), or publicly shame students for accruing unpaid meal debt [31, 32].

How can the NSLP respond in times of crisis?

School food authorities are limited in what they can do without prior approval from the USDA. During the COVID-19 crisis, the USDA responded with several flexibilities designed to streamline the provision of food to students. Some of the key flexibilities include [33]:

- Allow Meal Service Time Flexibility in the Child Nutrition Programs

- Allow Non-Congregate Feeding in the Child Nutrition Programs

- Waiver of the Activity Requirement in Afterschool Care Child Nutrition Programs

- Allow Parents and Guardians to Pick Up Meals for Children

Collectively, these waivers allow schools to provide meals and snacks to students without requiring the students to consume the meals on campus or be present when the meals are picked up. In addition, schools can apply for a Meal Pattern Flexibility in the Child Nutrition Programs waiver if needed [34].

Do ketchup and pizza count as vegetables in the NSLP?

A popular anecdote regarding school lunch is that President Reagan proposed that ketchup should count as a vegetable in school lunch. This was part of several new regulations proposed by the USDA during the Reagan administration to help programs lower costs as a result of budget cuts to the NSLP. One proposed rule would give state agencies discretionary authority to credit specific food items as long as they were reported to the USDA and consistent with regulations. One example in the proposed rule was that a state "could credit a condiment such as pickle relish as a vegetable” [2]. This led to a tremendous backlash [3] and this particular regulation was not in the final rule.

Following the release of the proposed rule to implement the HHFKA, a similar situation emerged with pizza. The proposed rule stated that tomato paste could only be credited as the volume served, while previously, due to tomato paste being more concentrated, 2 tablespoons could be credited as ¼ cup of vegetables. Before the final rule was released, an agricultural appropriations bill [5]included a provision applying to the NSLP that required tomato paste to continue to be credited as greater than the volume served. This was reported in the media as pizza being allowed to be credited as a vegetable, as a slice of pizza could contain 2 tablespoons of tomato paste and thus the tomato paste on the pizza could partially meet the vegetable component requirement [6].

References:

- Public Law: 79-396: Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act of 1946. (60 Stat. 230; 06/04/1946; enacted H.R. 3370).

- National School Lunch, School Breakfast, and Child Care Food Programs; Meal Pattern Requirements; Proposed Rule, 46 Fed. Reg. 44452 (Sep. 4, 1981) (to be codified at 7 CFE pts 210, 220, and 226. https://s3.amazonaws.com/archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1981/9/4/44447-44472.pdf#page=6. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- Sinclair W. "Q: When Is Ketchup a Vegetable? A: When Tofu Is Meat". The Washington Post, September 9, 1981, Wednesday, Final Edition. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:3S8G-CRN0-0009-W0HP-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed September 10, 2020.

- Nutrition Standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs; Final Rule, 77 Fed. Reg. 4088 (Jan. 26, 2012) (to be codified at 7 CFR pts. 210 & 220).

- Public Law 112-55: Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2012

- Dina ElBoghdady. "Effort to make lunches healthier derailed". The Washington Post, November 16, 2011 Wednesday. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:548C-2HW1-JBFW-C3XR-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed September 23, 2020.

- Moss M. "Pizza Goes to School". The New York Times, June 11, 2014 Wednesday. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:5CDC-DT21-JBG3-637V-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed September 23, 2020.

- Domino’s Smart Slice Brochure https://biz.dominos.com/documents/1697006/6681236/SmartSliceBrochure+-+updated+9.19.pdf/671e5f29-df92-be23-b6f8-a5cc8fc7f296. Accessed September 23, 2020.

- Domino’s School Lunch Nutrition. Domino’s Pizza Website.https://biz.dominos.com/web/public/school-lunch/nutrition Accessed September 23, 2020.

- Domino’s Pizza Website. Cal-O-Meter. https://www.dominos.com/en/pages/content/nutritional/cal-o-meter. Accessed September 23, 2020. .

- Congressional Research Service (2019). School Meals Programs and Other USDA Child Nutrition Programs: A Primer. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43783. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553 (2011).

- Ctr. for Sci. in Pub. Interest v. Perdue, Case No.: GJH-19-1004 (D. Md. Apr. 13, 2020).

- Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements; Interim Final Rule, 82 Fed. Reg. 56703 (Nov. 30, 2017) (to be codified at 7 CFR pts. 210, 215, 220, & 226). .

- Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements; Final Rule, 83 Fed. Reg. 63775 (Nov. 30, 2017) (to be codified at 7 CFR pts. 210, 215, 220, & 226). .

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Offer versus Serve Guidance for the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program.

- National School Lunch, Special Milk, and School Breakfast Programs, National Average Payments/Maximum Reimbursement Rates; Notice, 85 Fed. Reg. 44270 (Jul. 22, 2020)

- National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in School as Required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Final rule and interim final rule. 81 Fed. Reg. 50131 (Jul. 29, 2016). (to be codified at 7 CFR pts. 210 & 220).

- Hur, I., T. Burgess-Champoux, and M. Reicks, Higher Quality Intake From School Lunch Meals Compared With Bagged Lunches. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition, 2011. 3(2): p. 70-75.

- Taylor, J.C., et al., Comparisons of school and home-packed lunches for fruit and vegetable dietary behaviours among school-aged youths. Public Health Nutr, 2019. 22(10): p. 1850-1857.

- Caruso, M.L. and K.W. Cullen, Quality and cost of student lunches brought from home. JAMA Pediatr, 2015. 169(1): p. 86-90.

- Martin, J. and C. Oakley, Managing Child Nutrition Programs: Leadership for Excellence. Second Edition ed. 2008, Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- Ralston, K.L., et al., The national school lunch program: Background, trends, and issues. 2008, United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). 7 CFR Section 210.14(a).

- Price, ML. "Employees put on leave after school lunches taken". Associated Press Online, January 31, 2014 Friday. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:5BDM-VP51-DYN6-W10N-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed September 23, 2020.

- Washington NA. "Dinner lady sacked for giving free lunch to hungry girl; Thousands sign a petition for Dalene Bowden to be reinstated". telegraph.co.uk, December 24, 2015 Thursday. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:5HP0-PKX1-JCJY-G1V1-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed September 23, 2020.

- 2 CFR, Part 225, Appendix B, Item 15.

- Public Law 108-265: Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 (118 Stat. 729; Date: 6/30/04).

- Local School Wellness Policy Implementation Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Final Rule, 81 Fed. Reg. 50151 (Jul. 29, 2016) (to be codified at 7 CFR pts. 210 & 220). .

- California Education Code (EC) sections 49430-49434.

- Pupil meals: Child Hunger Prevention and Fair Treatment Act of 2017, California Senate Bill 250 (2017-2018), Chapter 726. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB250 Accessed June 2, 2020.

- Pupil meals: Child Hunger Prevention and Fair Treatment Act of 2017, California Senate Bill 265 (2019-2020), Chapter 785. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB265 Accessed June 2, 2020.

- Child Nutrition COVID-19 Waivers. USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Retrived from: https://www.fns.usda.gov/programs/fns-disaster-assistance/fns-responds-covid-19/child-nutrition-covid-19-waivers. Accessed September 14, 2020.

- COVID-19 Nationwide Waiver to Allow Meal Pattern Flexibility in the Child Nutrition Programs. USDA Food and Nutrition Service. https://www.fns.usda.gov/cn/covid-19-meal-pattern-flexibility-waiver Accessed September 14, 2020.

Inquiries regarding this publication may be directed to cns@ucdavis.edu. The information provided in this publication is intended for general consumer understanding, and is not intended to be used for medical diagnosis or treatment, or to substitute for professional medical advice.

California's CalFresh Healthy Living, with funding from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – USDA SNAP, produced this material. These institutions are equal opportunity providers and employers. For important nutrition information, visit www.CalFreshHealthyLiving.org.